Context Engineering: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Manage the Smart Zone

Context Engineering: How I Learned to Worrying Less and Manage the Smart Zone

Learning to treat AI coding assistants as amplifiers, not replaceholders, through a cost-saving Drupal 7 to Astro.js migration project

The $100k+ Opportunity

Six months ago, I thought I understood how to work with AI coding assistants. As a Senior Technical Lead at Fluke Corporation managing legacy website migrations, I’d been using Claude, GitHub Copilot, and various local AI tools to accelerate our work. We were tackling a critical business problem: converting aging Drupal 7 websites to modern Astro.js implementations, extending their SEO value and customer utility while potentially saving over $100,000 in migration costs.

My early approaches weren’t working—but then I found a framework that changed everything.

Dex Horthy’s talk “No Vibes Allowed: Solving Hard Problems in Complex Codebases” at the AI Engineer Code Summit introduced advanced context engineering principles that fundamentally changed how our team builds software—and how we’re capturing those cost savings.

The SpecKit Disaster: A Valuable Failure

Our first few attempts at AI-assisted migration used what seemed like a sophisticated approach: detailed specifications fed into AI tools to generate comprehensive implementation plans. We tried the SpecKit method—essentially asking AI to generate verbose, multi-phase migration plans upfront for entire site conversions.

It was a disaster.

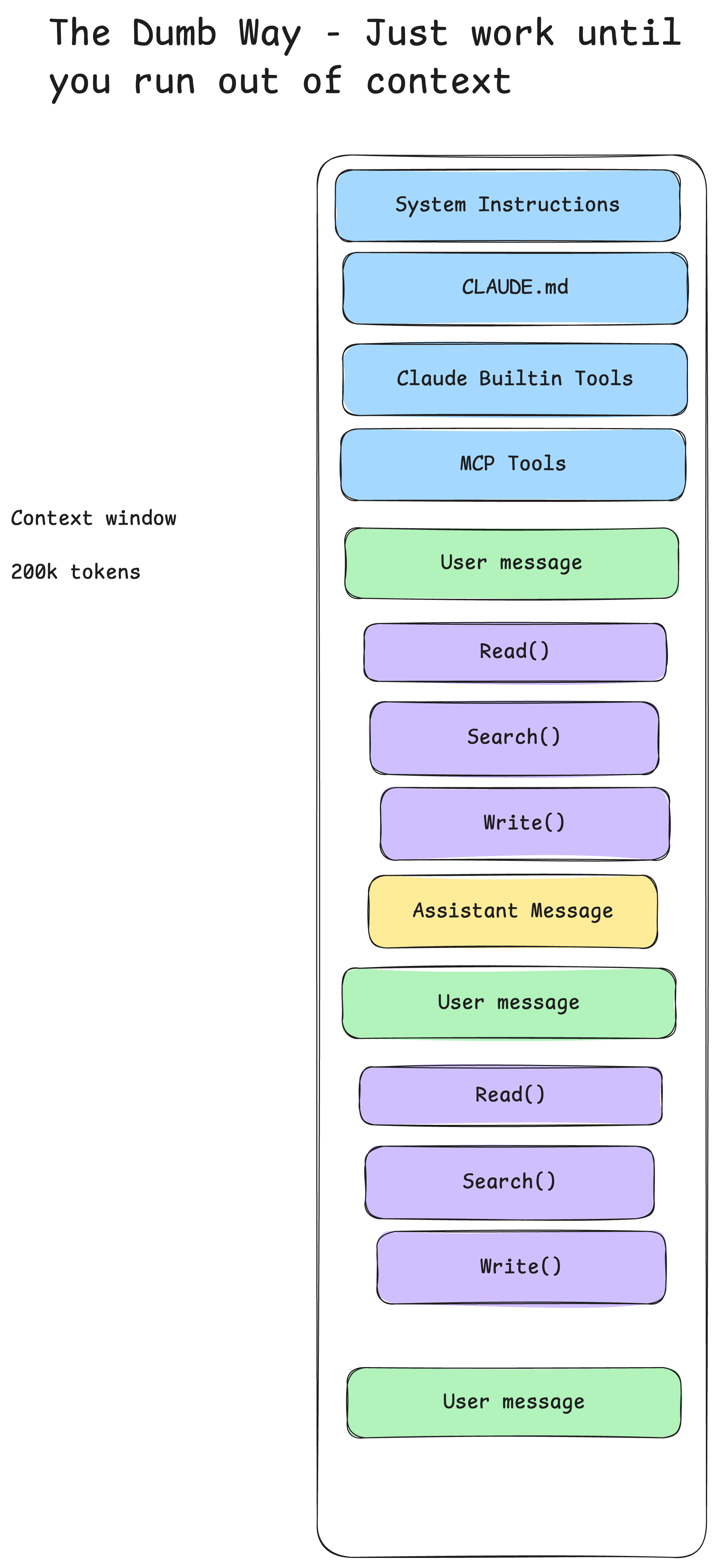

The AI would generate 40-50 step plans that looked impressive. Pages of detailed instructions. Specific file paths. Configuration snippets. But somewhere around step 15-20, everything would fall apart. The implementation would drift from the plan. Edge cases the AI hadn’t anticipated would surface. We’d iterate, the context window would bloat with corrections and re-corrections, and eventually we’d be stuck in what Dex calls “the dumb zone”—that zone beyond ~40% of your context window where model performance degrades significantly.

As Dex put it in his talk: “The most naive way to use a coding agent is to ask it for something and then tell it why it’s wrong and resteer it and ask and ask and ask until you run out of context or you give up or you cry.”

I was crying. A lot. Especially after letting it “vibe” for over 7 hours on a weekend.

But this failure became a valuable proof-of-concept. It helped me understand that the problem wasn’t the AI’s capabilities—it was our context engineering strategy.

Understanding the Dumb Zone

Dex’s presentation introduced a concept that better explained our obvious problems (that takes some humility and vulnerability to admit): the “dumb zone.” Here’s the core insight:

Around the 40% line is where you’re going to start to see some diminishing returns depending on your task. If you have too many MCPs in your coding agent, you are doing all your work in the dumb zone and you’re never going to get good results.

Source: Advanced Context Engineering for Coding Agents by Dex Horthy

Source: Advanced Context Engineering for Coding Agents by Dex Horthy

The diagram crystallized our problem: we were loading massive Drupal 7 codebases, existing migration attempts, comprehensive requirements docs, and verbose AI-generated plans all into the same context window. By the time the AI started writing actual code, we were deep in the dumb zone where “the more you use the context window, the worse outcomes you’ll get.”

The RPI Loop: Research, Plan, Implement

Dex’s alternative is elegantly simple but requires discipline: separate your work into distinct phases that intentionally compact context at each transition.

Phase 1: Research

Understanding how the system works, finding the right files, staying objective.

Instead of dumping an entire Drupal 7 site into context, we now use focused research prompts to understand specific subsystems. For our Astro migrations, this means:

- How does this Drupal module handle taxonomy?

- What’s the actual content model for this section?

- Where are the custom field formatters defined?

The output is a compact markdown document—not code, not plans, just truth about how the system actually works.

Phase 2: Planning

Outline the exact steps. Include file names and line snippets. Be very explicit about how we’re going to test things after every change.

This is where we compress intent. The plan includes actual code snippets showing what will change, not just descriptions of changes. As Dex emphasized: “A bad line of code is a bad line of code and a bad part of a plan could be a hundred bad lines of code.”

This phase is where we caught our biggest mistake: we were skipping human review of plans. We’d generate a plan and immediately implement it. Now we review plans as a team before implementation, catching architectural problems before they become hundred-line mistakes.

Phase 3: Implementation

Step through the plan, phase by phase.

With a vetted plan and fresh context window, implementation becomes almost mechanical. The AI isn’t thinking—it’s executing. This is exactly where you want it.

The Hardest Lesson: Don’t Outsource the Thinking

The most uncomfortable truth from Dex’s talk hit me personally:

Do not outsource the thinking. AI cannot replace thinking. It can only amplify the thinking you have done or the lack of thinking you have done.

I’d been treating AI as a thought partner when I should have been treating it as a powerful amplifier. When I gave it poorly-thought-through requirements, it amplified my confusion. When I let it generate comprehensive plans without deeply understanding the problem space first, it amplified my ignorance.

The fix required humility: pair programming. Not human-AI pairing—human-to-human pairing with AI as the accelerant. Two engineers, one problem, AI as the implementation accelerant. This surfaced a coordination challenge I hadn’t anticipated.

The Coordination Problem: Tool Chaos

Our team uses:

- GitHub Copilot in local IDEs

- Claude Code for complex refactors

- Gemini for specific analysis tasks

- Various local AI-augmented development tools

Each team member had developed their own prompting strategies. What worked in Copilot didn’t translate to Claude Code. The “best practices” one developer swore by produced garbage for another. We were inadvertently fighting each other’s context engineering approaches.

Dex’s advice echoed in my head: “Pick one tool and get some reps. I recommend against minmaxing across cloud and codeex and all these different tools.”

But we couldn’t standardize on one tool—different tasks genuinely benefited from different approaches. Instead, we needed alignment on principles:

- Context budget awareness - Regardless of tool, stay under 40% of context window before implementation

- Compaction discipline - Clear context between distinct tasks

- Research-first mentality - Understand the system before planning changes

- Human-reviewed plans - No AI-generated plan executes without human validation

The coordination isn’t perfect, but pair programming sessions have become our alignment mechanism. We’re building shared intuition about when to use which tool and how to structure work for each.

The SDLC Shift: Code Review Before QA

The most significant process change was also the scariest: introducing code review before QA.

Previously, our workflow was:

- Developer implements (with AI assistance)

- QA tests

- If broken, back to developer

- Code review on working code

Our reasoning was pragmatic but flawed: we had low confidence in AI-generated code and didn’t want to waste reviewer time on broken implementations.

Post-context-engineering, our workflow is:

- Research phase (human-reviewed)

- Plan phase (human-reviewed)

- Implementation

- Code review (focusing on plan adherence)

- QA

This seems backwards—why review potentially broken code? But here’s what we learned: reviewing plans catches architectural problems; reviewing implementations catches plan-drift problems. Both are cheaper to fix than QA-discovered bugs.

The mental alignment that Dex emphasized becomes possible. As he noted: “I can read the plans and I can keep up to date and I can—that’s enough. I can catch some problems early and I maintain understanding of how the system is evolving.”

For our Drupal-to-Astro migrations, this means reviewers can catch problems like:

- Using the wrong Astro content collection patterns

- Misunderstanding Drupal’s field structure

- Over-engineering solutions because the AI didn’t know simpler patterns existed

The Leadership Challenge: Weekly Chaos

Here’s the uncomfortable truth about being a technical leader during this transition: what I present to leadership changes weekly.

Last month I might have advocated for full Claude Code adoption. This month I’m explaining why we need different tools for different tasks. Next month? Who knows what new insight will emerge from our pair programming sessions.

It’s humbling to discover that what I think isn’t what the development team members agree with. But that disagreement—surfaced through actual collaborative work—is where real alignment emerges.

Dex’s warning resonates: “If you’re a technical leader at your company, pick one tool and get some reps.” But he also notes: “Cultural change is really hard and it needs to come from the top if it’s going to work.”

I’m trying to thread this needle: provide direction without mandating specific tools, encourage experimentation while building shared principles, and accept that this week’s best practice might be next week’s anti-pattern.

Concrete Wins: The $100k Proof

Despite the chaos, the results are undeniable. Our Drupal 7 to Astro.js migrations that once stalled for weeks now progress steadily. We’re:

- Preserving SEO value from legacy sites

- Maintaining customer access to valuable information

- Saving over $100,000 in migration costs

- Building team capability instead of vendor dependency

The SpecKit disaster taught us what doesn’t work. Dex’s framework gave us vocabulary for what does. Our pair programming sessions are turning principles into practice.

Key Takeaways for Technical Leads

If you’re managing AI-augmented development teams:

-

Expect your own mistakes - Your first approaches will probably fail. That’s the tuition for learning context engineering.

-

Research > Planning > Implementation - Separate these phases explicitly. Each should compact context for the next.

-

Review plans, not just code - Catch architectural problems before they become implementation problems.

-

Pair program for alignment - Different team members will develop different strategies. Pair programming surfaces conflicts and builds shared intuition.

-

Embrace weekly uncertainty - Best practices are evolving rapidly. Your leadership approach needs to accommodate that.

-

Don’t outsource the thinking - AI amplifies your intelligence and your ignorance. Make sure you’re giving it intelligence to amplify.

The Real Insight: Context Engineering is SDLC Engineering

Dex’s most profound insight wasn’t about prompts or tools—it was about process:

The hard part is going to be how do you adapt your team and your workflow and the SDLC to work in a world where 99% of your code is shipped by AI.

Context engineering isn’t just about managing token windows. It’s about redesigning your entire software development lifecycle around a new reality: AI doesn’t replace thinking, it makes thinking more expensive to skip.

Our Drupal-to-Astro migrations are teaching us this daily. Every shortcut we take in research creates downstream problems in planning. Every plan we implement without review creates technical debt. Every time we let context bloat into the dumb zone, we pay for it in wasted iteration cycles.

But when we do the thinking—real, hard, architectural thinking—and let AI amplify that thinking through disciplined context engineering? We ship in days what would have taken weeks, maintain quality that passes expert review, and save our company real money.

The future isn’t AI replacing developers. It’s developers who master context engineering replacing developers who don’t.

Resources

- Dex Horthy’s Talk: No Vibes Allowed: Solving Hard Problems in Complex Codebases

- GitHub Repository: Advanced Context Engineering for Coding Agents - Contains research/plan/implement prompts and examples

- 12 Factor Agents: HumanLayer’s principles for production AI

Kevin is a Senior Technical Lead at Fluke Corporation, where he manages web infrastructure, Drupal migrations, and international operations. He’s spent 20+ years in web development and is currently applying advanced context engineering principles to make AI-assisted development work.

About the Author

Kevin P. Davison has over 20 years of experience building websites and figuring out how to make large-scale web projects actually work. He writes about technology, AI, leadership lessons learned the hard way, and whatever else catches his attention—travel stories, weekend adventures in the Pacific Northwest like snorkeling in Puget Sound, or the occasional rabbit hole he couldn't resist.